Yuval Atzili | Death of a Nightingale

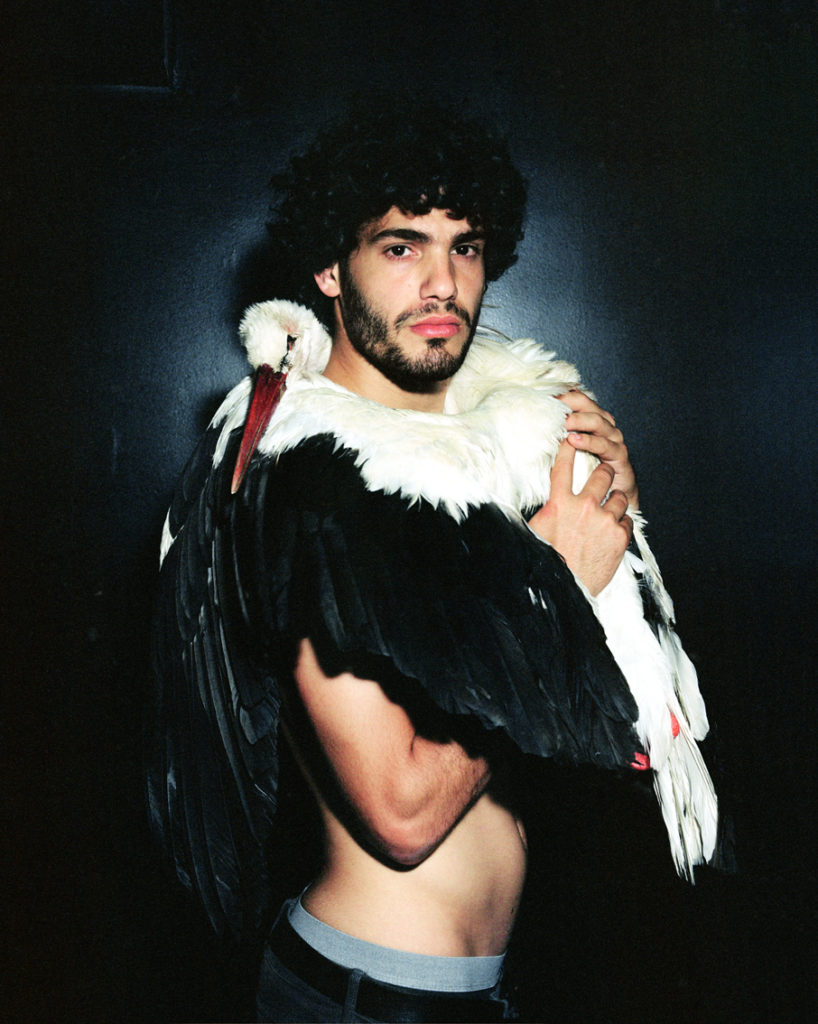

‘Photography is an elegiac art, a twilight art. All photographs are memento mori’ writes Susan Sontag in ‘On Photography’. She refers to a photograph’s essence, but the phrase ‘remember that you must die’ is strongly validated in Atzili’s work. The gallery displays seven large-sized portraits of half-naked men, each holding a bird. The birds are all dead. Six of the seven portraits were taken at a nightclub to which he took the photography equipment and the birds. He asked random men, who were, according to their appearance, between adolescence and young manhood, to be photographed with the bird. The background is dark and gloomy; a single beam of light illuminates the photograph, the frames are staged and meticulous. A performative theater is created between the photographer, the person photographed, the dead animal, and us, the observers.

Beauty is a significant aspect of Atzili’s work. It is found in the contours of the body exposed to observation, in the encounter between the naked male skin and the feathers softness, the living body accepting the dead body in its bosom, the cradling, protecting, bearing, supporting, serving hands. The flamingo is cradled in a defensive position, seems to be sleeping in the bosom of the man holding it. The stork wraps around itself and is hugged into a bare chest; the parakeet stands on the palm of the hand; the birds look alive. It isn’t apparent who the dead animal’s personification is guarding against death’s annihilation. The white heron is exceptional; its open and milky eye looking out lifeless. Its feathers whiteness stands out against the dark skin of the man holding it. The men have no names. The anonymity turns them into representations of masculinity in all its aspects.

The death in the exhibition is neither violent nor impure. What we perceive as perversion or dirtiness mainly reveals the principles of cultural sorting and organization. What is the boundary between hygiene and dirtiness, holiness and impurity? These are not absolute values. The thing itself, the naked body, the exposed skin, or the dead animal’s body have no internal characteristic that makes them dirty or impure. The preoccupation with death, life, the physical representation of masculinity, contamination and taboo, purity and danger, aesthetics and beauty, power and control are repeated in his work.

In this sense, it is possible to refer to the implicit physical contact and the homosexual relationship between the two portraits hanging next to each other – the man embracing the flamingo and the boy holding the hoopoe. The reference to the appearance of the relationship developing between the living human body and the dead animal body, as between the male bodies and themselves, is a reflection of hierarchy models that apply to the social system. Like with the attitude towards dirt and contamination, here also can be seen as an attempt to impose a method on an essentially disordered experience. Life, death, and sexuality. Order is for appearance’s sake only, created by exaggerating the importance of the differences between inside and outside, between male and female, between holy and impure, between what is allowed and forbidden to do, photograph, commemorate, show.

In the center of the space hangs a black and white photograph of a simple, bare iron bed with a mattress covered with a white sheet, a white curtain in the background, and a sculpted paper swan placed on the bed. The lack of color, the clean whiteness, the minimalist room, the exact and precise order violated only by the soft delicacy of the sheet’s folds and the curtain touching the floor, the splendor of the wings spreading swan, create an intimate atmosphere of almost sanctity through the whole exhibition. It becomes more precise with the triptych, which center is the photograph of the paper swan. To its right is a collage work of a hoopoe; to its left is a peacock – standard images of male birds. In churches and cathedrals, the altar decoration is usually done in the form of a triptych – a work of art consisting of three parts. The hoopoe is Israel’s national bird, familiar, rough, standard, and somewhat lusterless. Against it is the exotic, colorful peacock with the crown on its head, with its magnificent and vulnerable tail. Looking at both creates a tension reflecting the contrasts and poles present within the exhibition space, as a kind of subconscious of the fluidity of the concepts that Atzili handles in his works. So too, the sense of purity, cleanliness, and holiness clash with the gloom and dead birds in the portraits series. They all reside together in the space – diving and simple, life and death, holiness and impurity, ostentation and vulnerability.